Greater pensions have been at the top of the policy priority list for some time, as high expectations of replacement rates have underwhelmed, in turn mainly reflecting issues in the labor market (low participation, spells of unemployment, slowing wage growth, informality), demographics (unchanged retirement age, longer life expectancy), capital markets (gradually lower returns), and the effects of the pension fund withdrawals.

Even though changes to the pension system have been a policy priority for several years, the past two administrations have unsuccessfully attempted to reform the structure of Chile’s pension system mainly due to a lack of consensus on the distribution of any additional savings contribution, who will collect, invest, and pay out the pensions, and the interest of some of incorporating a pay-as-you-go component to the system. Having faced a deadlock on these issues in Congress in the past two administrations, the most recent reform to the solidarity pillar of the pension system was approved in February 2022, with the creation of the PGU that broadened the coverage and raised publicly financed pensions (with respect to the Pensión Básica Solidaria program, implemented originally in March 2008).

In a nutshell, the approved reform introduces several changes to Chile’s pension system:

1. Higher publicly financed pensions: The PGU would gradually increase to CLP250,000 from CLP214,296, according to age and specific characteristics of retirees. The PGU would be adjusted once a year according to annual inflation. The first payout would begin in roughly six months (September 2025) for retirees aged +82 years and other beneficiaries. New beneficiaries would kick in during September 2026 and then September 2027.

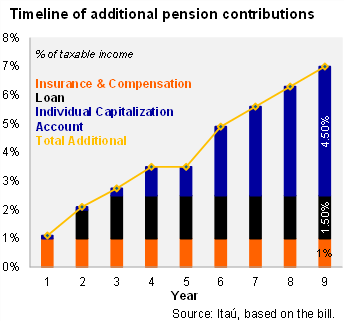

2. Additional pension savings: Pension contributions will gradually increase by an additional 7% of taxable income, nominally paid out by the employer. A total of 4.5 percentage points will go to the individual capitalization accounts, to be phased in by the ninth year; 1.5 percentage points will be loaned out to the State; and 1 percentage point will be used to increase pensions for women and provide an insurance.

3. Changes to the structure of the pension industry. The reform considers several changes to the pension industry that have the objective of enhancing competition, including lowering the barriers for new pension investment managers.

a.) Also, to foster greater fee competition among investment managers, 10% of the outstanding stock of affiliates would be randomly bid every two years, with affiliates allocated to the lowest fee (which will have to be maintained for the following five years); selected affiliates may decide not to shift to the new manager. Lower fees would not raise pensions per se under the current fee structure based on flows, rather would increase monthly income.

b.) Transition to a system of Targeted date funds: the current structure of five types of funds stretching from riskiest to most conservative would be replaced with targeted date funds, reducing the financial risks associated with the massive fund switching in previous years, among other effects. The reform creates a new system of ten generational funds, in which savers will be grouped in five-year cohorts while the worker is saving.

Our take: While far from a “first best”, we view the reform’s approval as positive on net:

• The approval reflects the possibility of reaching a broad consensus in Congress on structural reforms, despite an increasingly fragmented and polarized landscape, reducing uncertainty in a key industry and capital markets more broadly;

• The reform validates individual savings accounts as the main pillar of the pension system, delivers a much-needed boost (although gradual) to domestic household savings, and should gradually lead to a greater AUM;

• Unfortunately, the reform did not increase the retirement age, nor did it close the door to new withdrawals from individual savings accounts in the future;

Our main concerns are three-fold:

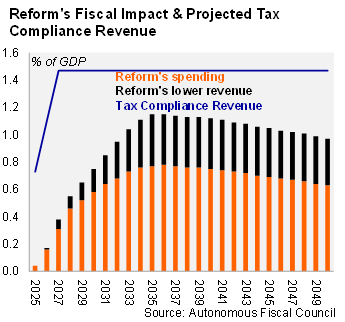

• Additional pressure on stressed fiscal accounts: The Autonomous Fiscal Council estimates that Chile has no fiscal space in the medium-term, that is, expenditures match structural revenues over time, leaving no room to accommodate shocks, persistent unanticipated and negative revenue shocks, or additional spending. In this context, the AFC projects additional fiscal spending due to the pension reform peaking in 2035 at roughly 0.8% of GDP and lower revenues at about 0.4% of GDP, leading to an overall negative fiscal impact of 1.2% of GDP. These are projected to be financed with an uncertain stream of permanent revenues of 1.47% of GDP sourced from the tax compliance law approved last year. Risks tilt towards fiscal costs being greater and revenues lower.

• Another headwind to the formal labor market recovery: Over the past few years several reforms have raised the cost of labor in Chile, including a minimum wage increase that has by far exceeded inflation and productivity estimates, and a gradual transition to a reduced work-week schedule, among others; the BCCh flagged the effects of these measures on the labor market in their December IPoM. With the unemployment rate trending slightly above the NAIRU, weak labor demand, and labor informality at roughly 27%, additional pensions contributions to be paid out nominally by the employer are likely to reduce wage growth, keep labor demand low, and add pressure towards higher informality. A MoF report confirmed that the reform would reduce formal employment in the long run by a cumulative of 0.7%, consistent with 100,000 fewer jobs; these effects could be compensated over time by the effects of higher GDP growth, investment, and savings.

• Uncertainty regarding the unintended consequences of industry changes: The broad set of changes to the industry are relevant, and implementation will need to be closely monitored to avoid unintended consequences. Lower barriers to entry (in the form of lower financial requirements, encaje in Spanish) should lead to new actors in an industry that has avoided financial scandals. Separately, some have voiced concerns saying that changes pave the path for a state-owned investment manager which was not approved in the reform; members of the governing coalition have stated they will present a bill that creates a state-owned investment manager as soon as March.